Europa Clipper flies above the icy surface of its namesake moon in this artist’s concept. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA’s newest science flagship is on its way to the Jupiter system to explore the icy moon Europa, one of the most compelling worlds in our solar system.

The mission began Oct. 14 from Launch Complex 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida at 12:06 pm EDT aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket. About an hour later, the spacecraft separated from its launch vehicle, embarking on a cruise through the inner solar system. A pair of gravity assists will eventually catapult it to Jupiter. The probe will travel approximately 2.9 billion kilometers over the next 5.5 years and reach the Jupiter system in 2030.

Related: The launch of Europa Clipper has been postponed until at least October 13 due to Hurricane Milton

Europa Clipper was originally scheduled to launch on October 10, but was delayed by Hurricane Milton. The craft made the hurricane’s destructive journey across Florida on the night of October 9-10, safely stowed in a hangar. After a damage assessment and recovery team surveyed the damage, Kennedy Space Center was declared safe and open, with only minor damage.

Enigmatic Europe

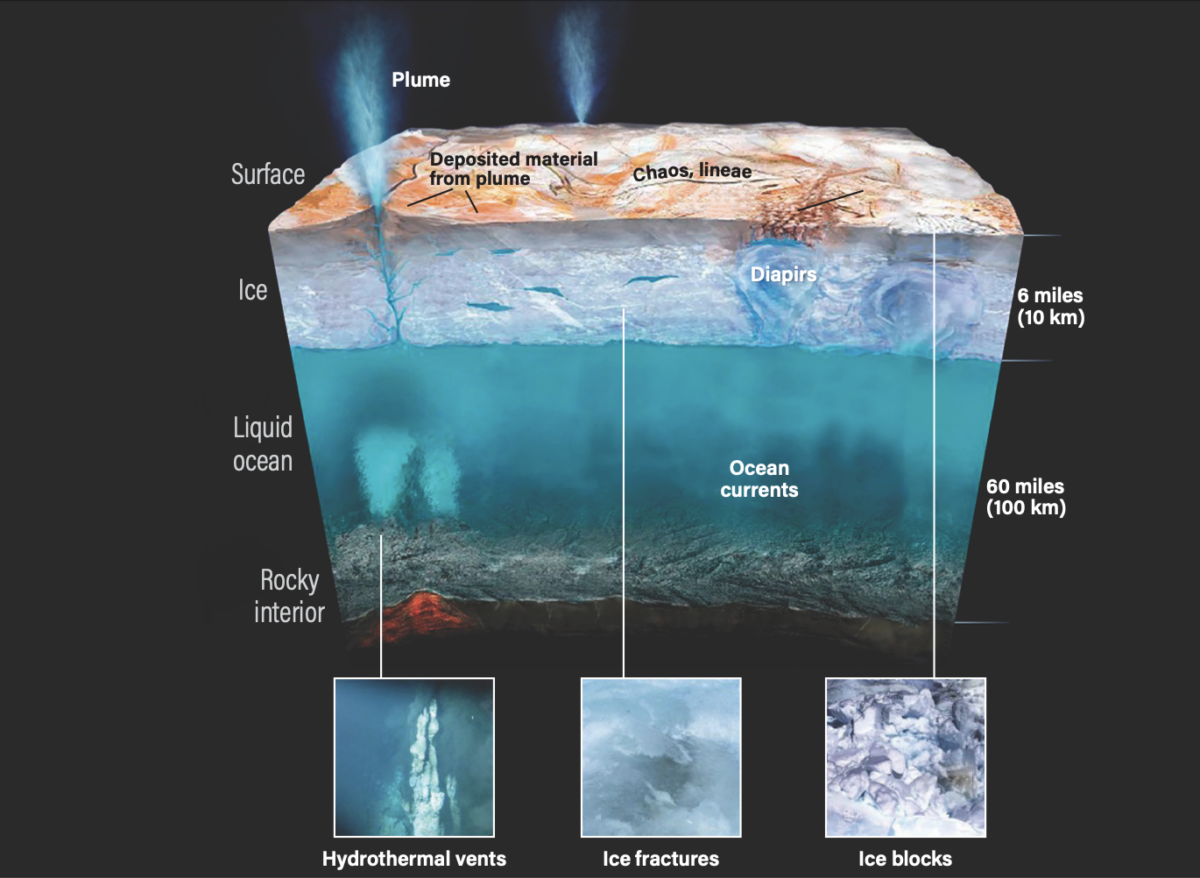

Europa, one of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons, has long fascinated scientists. The satellite, about 90% the size of our Moon, is believed to host a global ocean of liquid salt water, twice the volume of Earth’s oceans, but locked beneath a crust of water ice 2 to 20 miles thick (from 3 to 30 km). Not only that, the Moon is heated by tidal bending as it orbits Jupiter on an elliptical path and also contains the chemical building blocks of life as we know it.

All of these factors combine to create a compelling world into which Earth-like life could find a way. In fact, when people think about potentially habitable places within our solar system, Europa probably tops the list.

It is important to note, however, that “Europa Clipper is not specifically a life-seeking mission.” Instead, “we will understand the potential habitability of Europa,” Europa Clipper project scientist Robert Pappalardo said in a NASA video. The mission will use nine instruments to study the interior and exterior of the Moon, as well as the environment in which it is located, to learn about the ice shell and the ocean it hides, as well as the composition of the Moon and whether it is geologically active. .

A dedicated mission

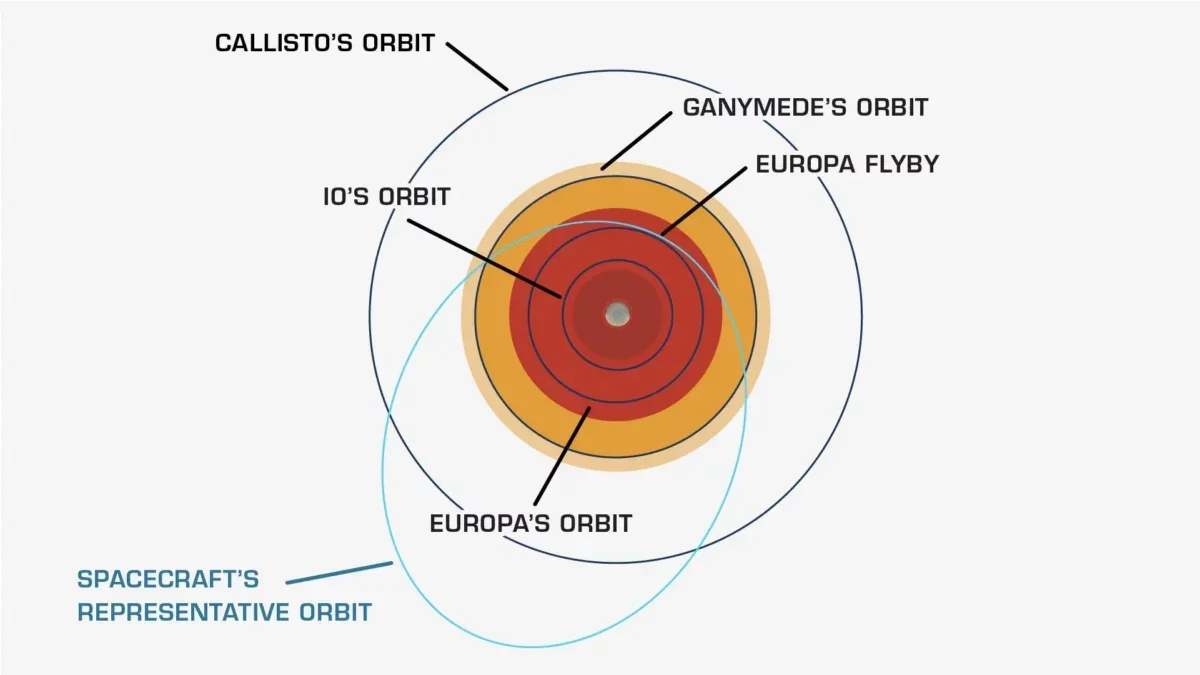

Once launched, Europa Clipper will complete a triad of Jupiter missions currently in action, joining NASA’s Juno, which has been orbiting Jupiter since July 2016, and ESA’s JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE), which launched in April 2023 and he is also on a mission. road to the gas giant. In fact, Europa Clipper, whose arrival at Jupiter is currently scheduled for April 2030, will arrive before JUICE at its destination by about a year thanks to different trajectories.

Related: The JUICE spacecraft goes on a mission to explore the icy moons of Jupiter

But why send Europa Clipper, if Juno is already in orbit and JUICE is on the way?

Juno is dedicated to the study of Jupiter itself, although it has certainly sent back some stunning images of the moons as well. Additionally, Juno’s mission is coming to an end, scheduled to conclude in September 2025. And after JUICE’s arrival in 2031, it will complete just two flybys of Europa in July 2032, before moving on to focus the majority of its mission to Ganymede and Callisto. . Like Europa, these larger moons also presumably host liquid oceans underground, albeit deeper beneath their own icy crusts.

Now, “for the first time ever, we are sending a spacecraft completely dedicated to studying this moon,” said Tracy Drain, Europa Clipper’s chief flight systems engineer.

After launch, Europa Clipper’s journey will take it past Mars (2025) and Earth (2026) to receive gravitational assistance before reaching the Jupiter system. Once there, it will use the Galilean moons to slow and shape its orbit, aiming to resonate with Europa’s orbit and make its first flyby of Europa’s moon in early 2031. Shortly thereafter, in May of that year, the spacecraft will begin its science. campaign, focusing first on the anti-Jupiter side of the Moon (the side of Europa facing away from Jupiter).

A second science campaign, which will send the probe beyond the Jupiter-facing side of the Moon, will begin in May 2033. In all, Europa Clipper will make 49 flybys of Europa, each passing over different terrain as it builds a nearly complete global globe. surface map. At its closest point, it will skim just 16 miles (25 km) above the surface.

During these campaigns, the spacecraft will immerse itself in one of the worst environments imaginable, bathed in the intense radiation surrounding Jupiter. The massive planet supports an extensive magnetosphere, the region of space where its magnetic field dominates. Charged particles from both the Sun and Jupiter itself, as well as the highly volcanic moon Io, are trapped by the planet’s powerful magnetic field and generate huge, intense radiation belts – belts that include Io, Europa and Ganymede, with the two largest internal orbiting moons in the worst case scenario.

While there’s no way to avoid this environment if you want to study Europa – and indeed, scientists think this unique environment actively shaped Europa into the world we see today – the mission is taking precautions. First, the spacecraft will orbit Jupiter rather than Europa, meaning it will fly through — but not continuously stay within — the worst of the radiation. However, according to NASA, during each flyby, Europa Clipper will experience a radiation dose equivalent to 1 million chest x-rays.

That’s why Europa Clipper also takes a design note from Juno: The aircraft’s computer and sensitive electronics are enclosed inside a sealed central vault, whose aluminum-zinc walls are about ⅓ of an inch thick (9.2 millimetres). According to NASA, these walls will keep out enough punishing radiation and fast-moving particles to ensure that the electronics inside experience only “acceptable” levels of radiation and can function for the duration of the mission.

In May, however, engineers expressed concerns about the spacecraft’s transistors and their ability to withstand the high-radiation environment in which they were traveling. It appeared that parts might be less resistant to radiation than expected and some would fail prematurely. However, further testing ultimately demonstrated that the transistors would support the intended mission duration.

Additional specifications

Europa Clipper is NASA’s largest spacecraft ever built for a planetary mission. It weighs about 13,000 pounds (5,900 kilograms) and, with its two large solar panels extended like wings, spans more than 100 feet (30.5 meters), about the length of a basketball court.

The mission carries visible-light and infrared cameras, as well as ultraviolet and infrared spectrometers to measure composition. Its magnetometer and plasma instrument will measure the Moon’s magnetic field (generated by its motion through Jupiter’s changing magnetic field). These observations will confirm the presence of a subterranean ocean, as well as measure its salinity, depth and even the thickness of the ice shell above it. A radar instrument will also help map the surface, determine the thickness of the icy crust, and even collect underground liquid to confirm the presence and depth of the ocean.

Gravity science experiments will allow astronomers to assess how Europa Clipper’s flight path changes as it is affected by the moon’s gravitational environment, which changes as it orbits Jupiter. This, in turn, will reveal how much the Moon’s shape changes due to tidal forces, a factor intrinsically linked to its internal structure.

Finally, the mass spectrometer and surface dust analyzer will explore the environment around the Moon. In particular, they will analyze the material emitted by the geysers, as well as the surface ice particles thrown into space by micrometeorites. By directly studying the chemistry of Europa’s surface ice and groundwater, scientists will be able to determine whether its ocean might actually be hospitable to life.

Answers in advance

“All these worlds are yours, except Europa. Do not attempt to land there,” reads the radio message broadcast to Earth at the end of Arthur C. Clarke’s 2010: odyssey two. Although fueled by the presence of fictional plant-like creatures beneath Europa’s surface, the sentiment behind the message rings true in real life. After just under a year and a half of scientific studies, Europa Clipper will end its mission in September 2034 with a “deorbit” towards its companion Galilean moon, Ganymede.

But Ganymede, like Europa, also hosts an underground ocean. So why was he targeted for the incident? According to ESA, whose JUICE mission will also eventually hit Ganymede: “The icy moon Europa is the only object believed to have the potential to host life, and therefore needs to be protected. … But as it stands, planetary protection rules allow a crash into Ganymede, because there are no indications that Ganymede’s deep subsurface ocean could be in contact with the icy surface. The crash on Europa would not be allowed because it is suspected that Europa’s underground oceans are shallower and therefore contamination from the surface to the ocean would theoretically be possible.”

Related: Why did Cassini crash into Saturn?

Despite the brevity of the mission, Europa Clipper has the potential to unlock one of the most mysterious and alluring worlds in our solar system. And it will surely bring us one step – or perhaps several steps – closer to answering the question of whether Earth is the only world in the solar system hospitable to life.

“This mission has been long overdue and we are so excited about what we will see once we arrive,” Pappalardo said.

Editor’s Note: This story was updated Oct. 15 to include information about the Europa Clipper launch and the status of recovery efforts at Kennedy Space Center.