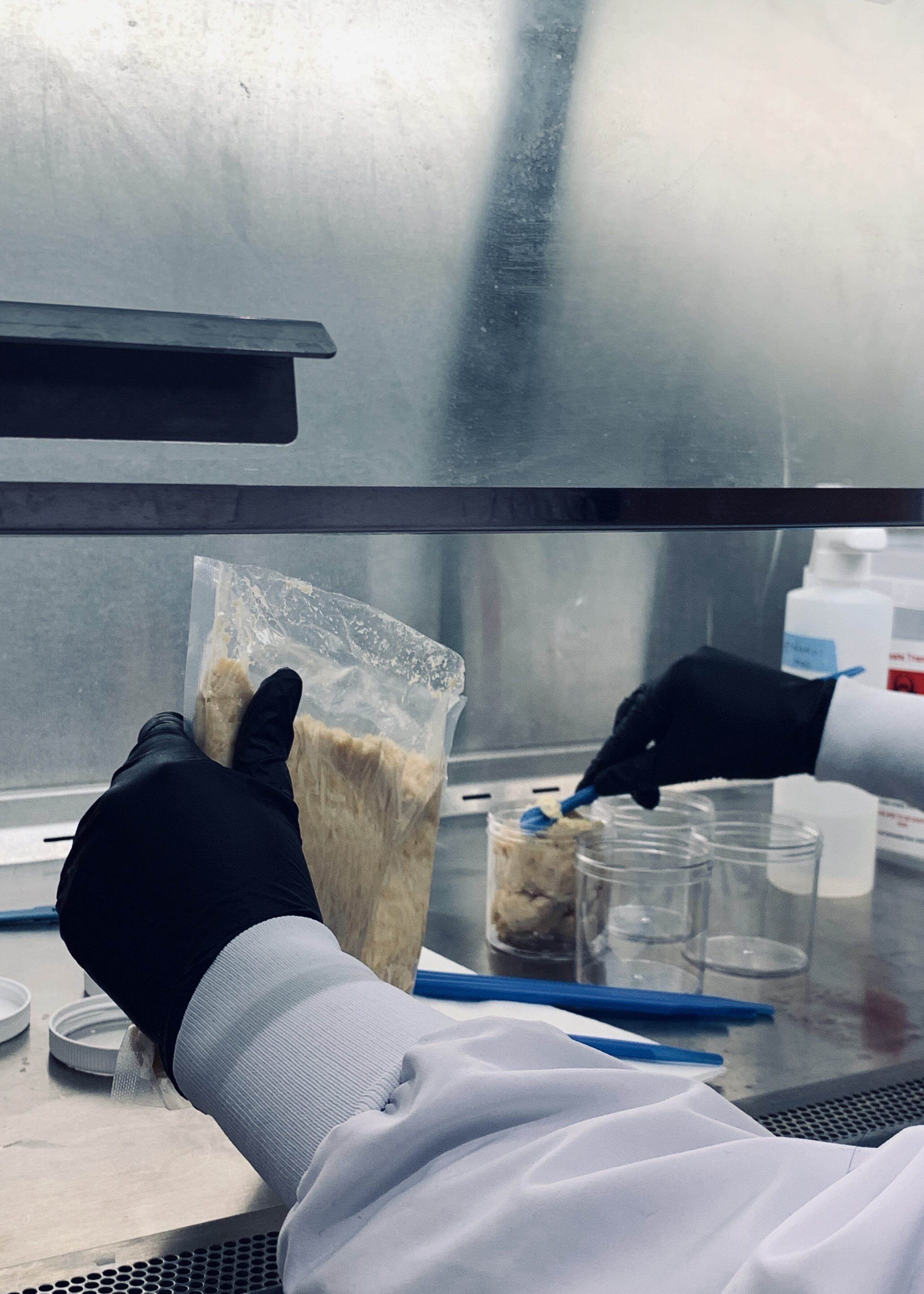

The researchers are exploring as fermented foods like miso could become part of the diets of astronauts. Credit: Maggie Coblentz

Takeaway Keyway:

- A study successfully fermented Miso on the International Space Station (ISS) for 30 days, demonstrating the feasibility of the fermentation of the space.

- The ISSO ISS has shown significant differences in the profiles of the flavor (NUTTER) and microbials and chemicals compared to the controls fermented by the earth.

- The variations have been attributed to several factors, including an increase in the unexpected temperature within the ISS detection box, but the exact cause remains indeterminate.

- “Everything we can say is that it is different from here. But there are so many reasons why they could be, and they are probably all those things that work together,” said Maggie Coblentz.

The ancient culinary practice of fermentation can play a role in the future of space cuisine.

In March 2020, an interdisciplinary team of researchers sent a small lot of ingredients for the Japanese Miso seasoning at the International Space Station (ISS). In the first experiment of its kind, the miso spent 30 days to ferment aboard the laboratory in orbit and was flew to Earth for further analyzes, including taste tests.

The participants in the study discovered that the fermented lotto lot had the characteristic salty flavor of miso, but had a significantly hazelly flavored flavor than the identical lots that had remained on earth to ferment. There were also differences in microbial and chemical profiles, they discovered researchers.

In an article published in IRCHIENCE On April 2, the team reports that it cannot be sure what the differences caused exactly. But, they say, it shows that the food that ferments in space is feasible – and that could lead to healthier and tastier food for astronauts.

A new frontier for fermentation

The “Space Miso” project was started by Maggie Coblentz, a researcher at the Mit Space Exploration Initiative and co-conductor of the study. “I was thinking of expanding food products for astronauts beyond the liophilized military ration style,” he said.

The fermentation emerged as a possible way when Coblentz started collaborating with the food researcher Josh Evans of the Denmark Technical University. They wondered if the fermentation of foods in space could provide a way to bring more flavor, microbial diversity and nutritional value to the astronaut diet.

On earth, the demand for fermented foods and drinks is growing, from Kimchi to Kombucha, led partly by the interest in their contributions to intestinal health and sustainable food practices.

But it was not known on how fermentation would work in space. The experiments conducted in the workshops on earth had suggested that microgravity could alter the process. But the fermentation on the ISS had not been tempted before.

RELATED: A scientific salad for astronauts in deep space

When the opportunity emerged to send an experiment in space, the team has chosen to send a fermented miso for some reasons.

The first was practical, says Evans. As a pasta, it is less likely to loss of fermented drinks, reducing the risk of damaging other experiments and ISS equipment. And the fermentation process for miso was suitable for the 30 -day window they had available for the experiment.

There have also been scientific considerations, adds Evans, who studies how several microbes of microbes influence the flavor of fermented foods. A recent wave of research on the fermentation of the miso has allowed the team to compare their fermented miso in space and put their results in the context.

Then there were the culinary reasons: used in soups, sauces and marinated, Miso is nourishing, has a strong taste of umami and a rich cultural history.

Bring fermentation into space

Miso is made with cooked soybean seeds, salt and Koji – a fermentation appetizer made with a wheat like rice or barley that has been inoculated with a mushroom called Aspergillus Oryzae.

“The overall process has two main steps,” said Evans. “First the Koji grows, which needs air. So when the ingredients mix and packed the mixture in the fermentation container, the salt and the lack of oxygen kill the koji and allows bacteria and salt tolerant to continue to continue fermentation.”

Those bacteria break down sugars in the initial mixture in other compounds, including those that give Miso its salty flavor. The specific flavor of a miso can vary according to the unique microbial culture of a lot, as well as a variety of environmental factors that could be different in space.

For the experiment, the team in Denmark has prepared a lot of miso of about 2 kilos (1 kilogram) and divided it into three portions. In March 2020, a part went to the ISS for 30 days, one went to Coblentz in Massachusetts and one remained in Denmark with Evans.

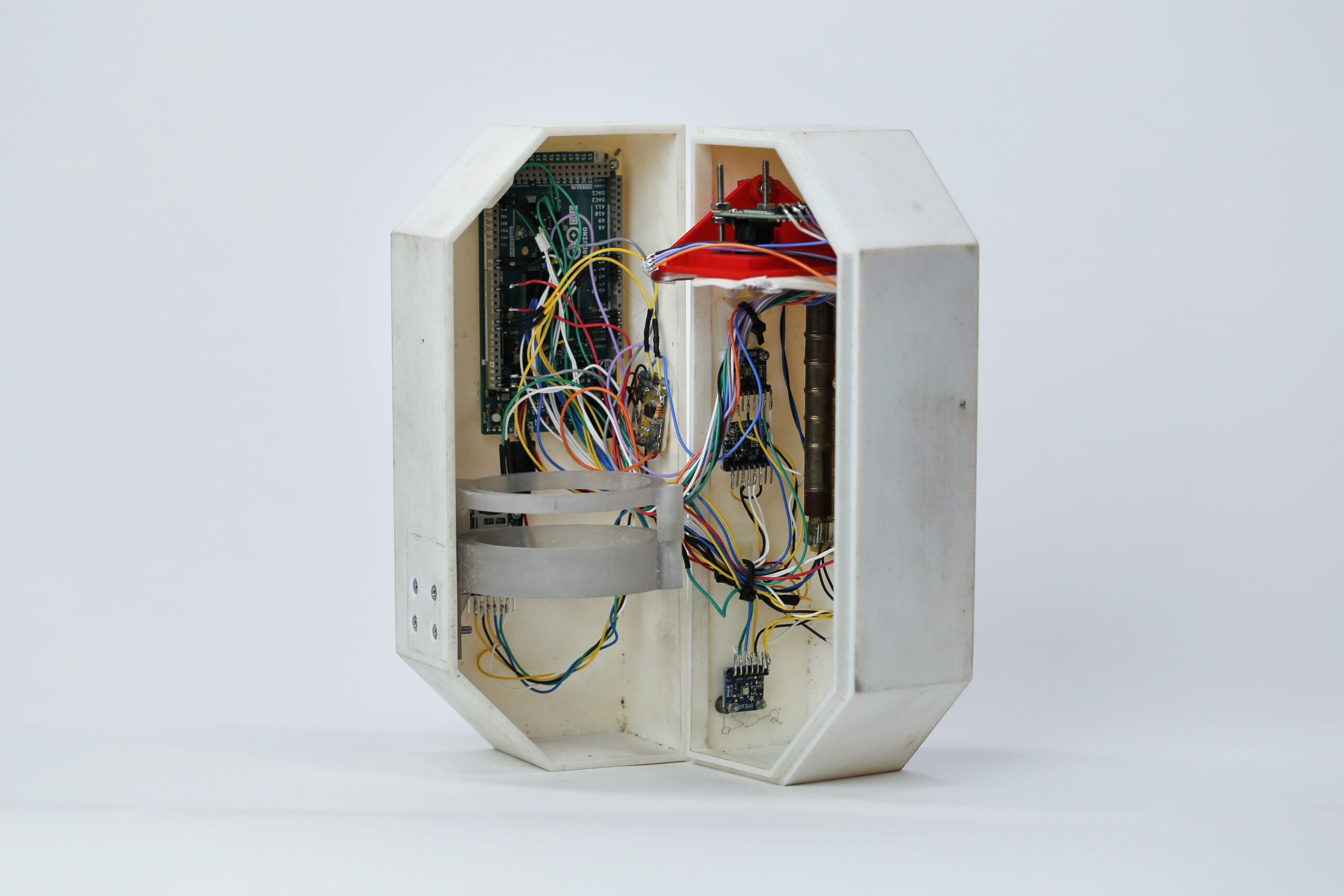

To monitor the space environment, Coblentz and Evans brought food engineers and scientists to the team. They built what they called “detection boxes” for the portions of miso who went to space and remained in Massachusetts. The boxes recorded temperature, humidity, pressure and radiation in the environment during the 30 -day fermentation process.

All three lots were frozen before and after the 30 -day experiment window to minimize the differences between the lots.

Test test

The Miso space was not consumed on board the ISS. But working to identify potential challenges or security problems involving fermented foods in space, the team hoped to bring them closer to the ISS menu.

When the team analyzed the microbial crops of Misos in the Evans laboratory, they discovered that the three microbial communities of Miso were similar and had most of the species in common, almost all from the kind of Stafylococcus. However, only the fermented miso on the ISS contained a species known as Bacillus Velezensiswhich had previously been identified in fermented soy foods. The authors think that this may be due to the fact that the temperature inside the detection box aboard the ISS has unexpectedly climbed to 97.3 degrees Fahrenheit (36.3 degrees Celsius) – compared to the portions on the earth, which were kept between 68 and 77 f (20 to 25 c).

The different misos also had differences in aroma and flavor. A group of 14 panelists that the team assembled described the Miso space as a roasted aroma, roast and a flavor of umami stronger than the two evils of the earth.

These differences may have been reflected in the chemical compounds found in misos. The Miso space contained higher concentrations of compounds with similar cheese aromas (2-metalbutanoic acid) and honey similar flavors (Metil Fenilacetate).

Future Frontiers

While the authors of the study have concluded that Miso could be fermented in space, they are not sure of how or if factors such as microgravity and radiation have influenced the specific properties of Formalting Miso. Then there was the unwanted heat that reached the miso, in addition to an accidental race with high forces G to and from the orbit and other environmental differences.

“Everything we can say is that it is different from here. But there are so many reasons why they could be, and they are probably all those things that work together,” said Coblentz.

The researchers want to understand how these factors have changed the miso before astronauts actually begin to ferment their ingredients. The food supplies of astronauts are strictly controlled because the risks of getting sick in space are much higher than on earth. For example, when Kimchi was transported by plane to the ISS in 2008, he was skipped with radiation before flight to kill the bacteria and prevent the cabbage from continuing to ferment on board. The unexpected change in the miso temperature shows that the fermentation process has not been kept under perfect control – something that should have been faced when they bring fermented food to the ISS.

Fermentation is a naturally sensitive process to change in its environment, observes Andrew Macintosh, an expert in fermentation at the University of Florida who was not involved in the study. “The space opens a completely new avenue,” he said. “And much of the value we see in this document are the difficulties that these researchers have faced in an attempt to collect information on how the space would be different.”

Macintosh sees this as a step towards a possible future in which the exploration of the space could be more self -sufficient and less dependent on the deliveries from the earth. The microbial communities involved in fermentation could be exploited and designed to produce food ingredients and even pharmaceutical products, think.

Coblentz says that their work could also help make the space more welcoming for travelers offering more choices for food, either through production through fermentation or simply improving its flavor. “Drawing on our deep earthly work history with food and fermentation in different cultures all over the world – has a sort of poetic appearance,” he said.