The Yerkes Observatory is located atop a hill in Williams Bay, Wisconsin. All photos were taken by Samantha Hill

The town of Williams Bay, Wisconsin is much like any other small town on a lake, with plenty of tourist shops and an active beach. But just a short drive after the activity brings you to the Yerkes Observatory. Behind an opening of trees lies a vast, grand estate with a well-manicured lawn and a large ornate building that stands proudly atop a small hill overlooking the water.

Although one of the most ornate buildings in southern Wisconsin, the Yerkes Observatory fell out of favor with its previous owner, the University of Chicago, due to its expensive maintenance and less-than-ideal location. The school eventually closed the observatory in 2018. However, the Williams Bay community was adamant that the property would not become another strip mall or generic apartment building. Instead, the Yerkes Future Foundation was born. Thanks to money raised from various donors and locals, the historic observatory reopened its doors to the public in 2022. The foundation now uses this historic site as a bridge to future scientific explorations.

Create a legacy

In 1892, the eminent astronomer George Ellery Hale founded the astronomy department at the newly formed University of Chicago. At about the same time, the school came into possession of the largest telescope in the world, the 40-inch refractor, following the display of the telescope’s mount and tube at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. With the largest refractor largest in the world and a new program underway, the school set about creating an observatory. The creation of the Yerkes Observatory was the result of money courtesy of Charles Yerkes, “the most hated man in Chicago.”

Yerkes, the major financier of streetcar systems in Chicago at the turn of the century, was known at the time for kicking people out of their homes, taking bribes, and having multiple affairs, among many other abhorrent behaviors. In an effort to increase his standing within the city’s high society, he donated the funds to build the observatory, as long as it was built within 100 miles of Chicago. And although he visited the observatory only once when it opened in 1897, and left the Midwest to distance himself from his misdeeds, his name lives on today. (His face can also be found on the exterior of the building in some decorative gargoyles depicting Yerkes himself. Other gargoyles depict the university’s former president, William Harper, as well as the unflattering and embellished features of John D. Rockefeller.)

Hale’s influence over the years led the university’s astronomy department to develop a robust astrophysics program complete with laboratories, offices, classrooms, and multiple observation areas. And its enormous refractor was the largest telescope in the world for nearly a decade, and remains the largest refractor ever built. Hale was not the only big-name astronomer to study or work for the institution at one time or another. The list also includes Carl Sagan, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, Nancy Grace Roman, Edwin Hubble and Edward E. Barnard.

In the 1960s Yerkes added a 41-inch reflector to the observatory. However, as the years passed, technology made rapid advances and ever-increasing light pollution affected the observatory, and the staff focused more on astrophysics. This work included efforts toward NASA’s now-retired Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA).

When the university donated the observatory to the conservation group in 2019, it had already attempted to sell the property to real estate developers. However, due to strong community protest, the observatory remained the property of the school before handing it over to the foundation.

Time capsule

I recently visited the Yerkes Observatory. When I entered the building, the experience almost reminded me more of a church or library due to the delicate arrangement of stones, its mythological creatures, celestial motifs, religious iconography and other unique designs lining the ceilings . This appears to be at odds with the many hands-on scientific instruments within the building.

During a tour of the building (which is open to the public for a fee), it was clear that the Yerkes Foundation wants to faithfully preserve the building’s history. This includes a treasure trove of glass plates featuring priceless images of the cosmos.

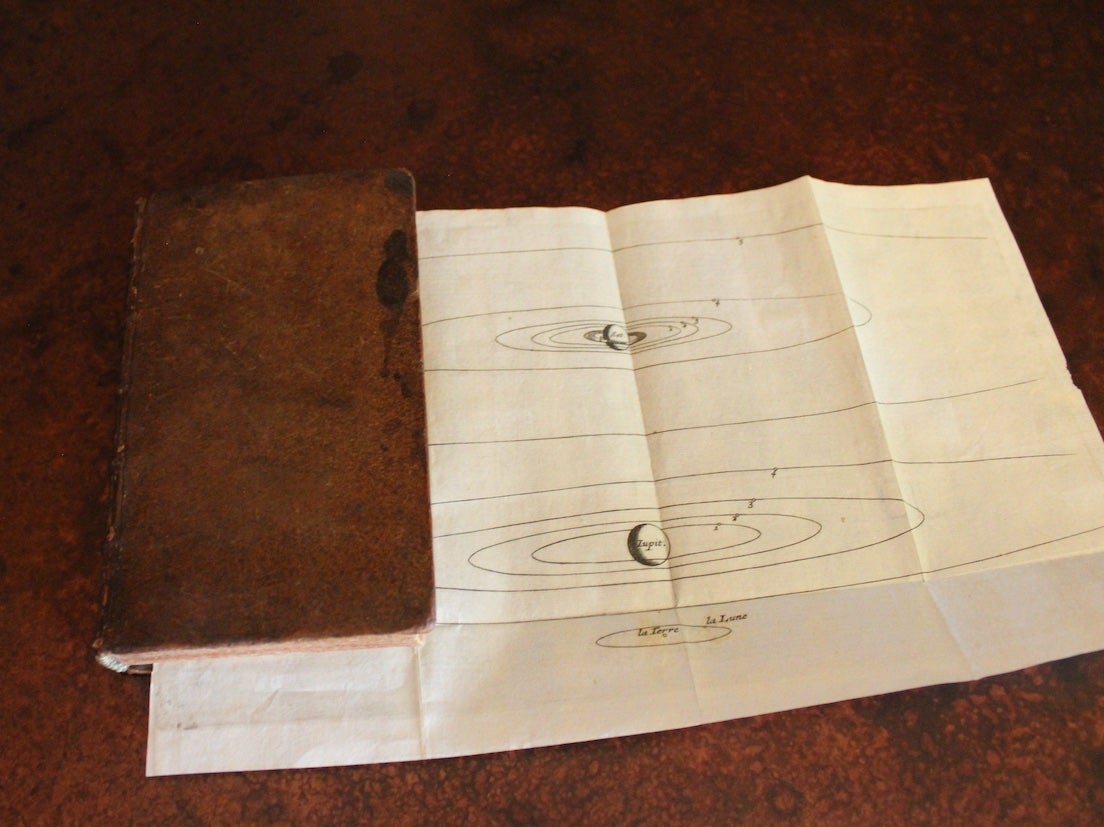

In the early days of observation, glass plates, usually the size of an average picture frame, were coated with light-sensitive chemicals and then exposed to light in a telescope or camera for long periods, capturing faint images of the sky. This meticulous process was an important aspect of data collection because often multiple plates of the same objects were taken and then compared to show any changes. The 180,000-piece collection contains a bevy of objects such as comets, spiral galaxies, star clusters and planets. The glass in one of the observatory windows was also used as a quick replacement for a plate during a solar eclipse and remains in its original position today.

With the advent of digital processing, glass plates have become obsolete. Only until recently have plates become archival tools, preserving significant time capsules of changes in stars, galaxies and nebulae over time. Through internship programs for students and volunteers, the Yerkes Foundation hopes to eventually digitize the collection.

Through a maze of corridors, stairways and Hale solar observing devices, visitors to the observatory are taken to the 41-inch reflector dome. Although the telescope still works, it is now operated by computer: the electrical panel located next to the telescope is for show only, and still looks similar to how it did when it was installed more than half a century ago.

As our group examined the telescope, we were reminded of how the dimensions of most modern telescopes have changed. “Remember the size of this when we go to see the other telescope,” Dennis Kois, executive director of the Yerkes Foundation, said during the tour. The dimensions between the two, we soon discovered, were incomparable.

As the tour group moved to the main dome where the Great Refractor is housed, it was clear that this bright blue telescope dominated the room. The size of a school bus, it is still functional after 130 years, along with the 120-ton dome that tops it.

With such a large telescope came complications, such as the distance of the eyepiece from the ground. The solution to creating a comfortable viewing position wherever the telescope was pointed was a mechanism that transformed the floor surrounding the telescope into a giant elevator. It was daytime when I visited, but the observatory offers visitors the chance to explore the cosmos at night.

Telescopes aren’t the only equipment the observatory continues to hang on to. In one room you can find a collection of early desktop computers, and in another room in the basement you will encounter several large pieces of engineering equipment used to solve problems and fabricate the necessary observation instruments. In another room there was still a collection of astronomy books, vintage binoculars, works of art and an old bicycle with fat tires used on trips to study the sky in Antarctica. Kois even laughed at an old George Foreman grill they kept, joking that Hale and his associates made a sandwich on it.

All of these objects were preserved with the goal of preserving as much of the foundation as possible to promote the observatory’s past.

Changing hands

After donating the property, the Yerkes Future Foundation continually worked to update several aspects of the building and the surrounding 50 acres of land, of which there were many. When the foundation took ownership of the property, the floors were brown due to layers of loose wax, the walls were tinged with cigarette smoke and even some offices had remained untouched for years.

With $23 million in funding, the foundation has launched an effort to revitalize the site and make it accessible to visitors. During the two years from purchasing the property to opening the facility’s doors, upgrades included adding solar panels, creating meeting rooms and event spaces, and cleaning and organizing items dating back 130 years ago and installing new bathrooms.

Amanda Bauer, Yerkes’ science and education manager, says they have a lot of plans for the next 10 years. With hopes of acquiring an additional $17 million in donations, the foundation will renovate the Great Refractor, replacing its brick foundation and repainting it, along with other projects such as plate digitization and other student programs.

The foundation keeps the community engaged and raises capital with programs such as tours of the facility, speakers such as former astronauts, and opportunities for visitors to use the telescopes. One of the most unique aspects of their revitalization effort includes the incorporation of art into the fabric of the observatory. High-contrast photos of broken sheets of glass line the hallways, while sculptors, painters and musicians have all held residency programs that blend the concept of science with art.

Despite its now heavily polluted location, the Yerkes Observatory retains great value. Historic architecture, research and community programs inspire visitors with a great sense of pride. Yerkes has gone from being an unhoused observatory to a home for the past, present and future of astronomy.

To learn more about the programs the foundation offers or if you would like to donate, visit: https://yerkesobservatory.org/.