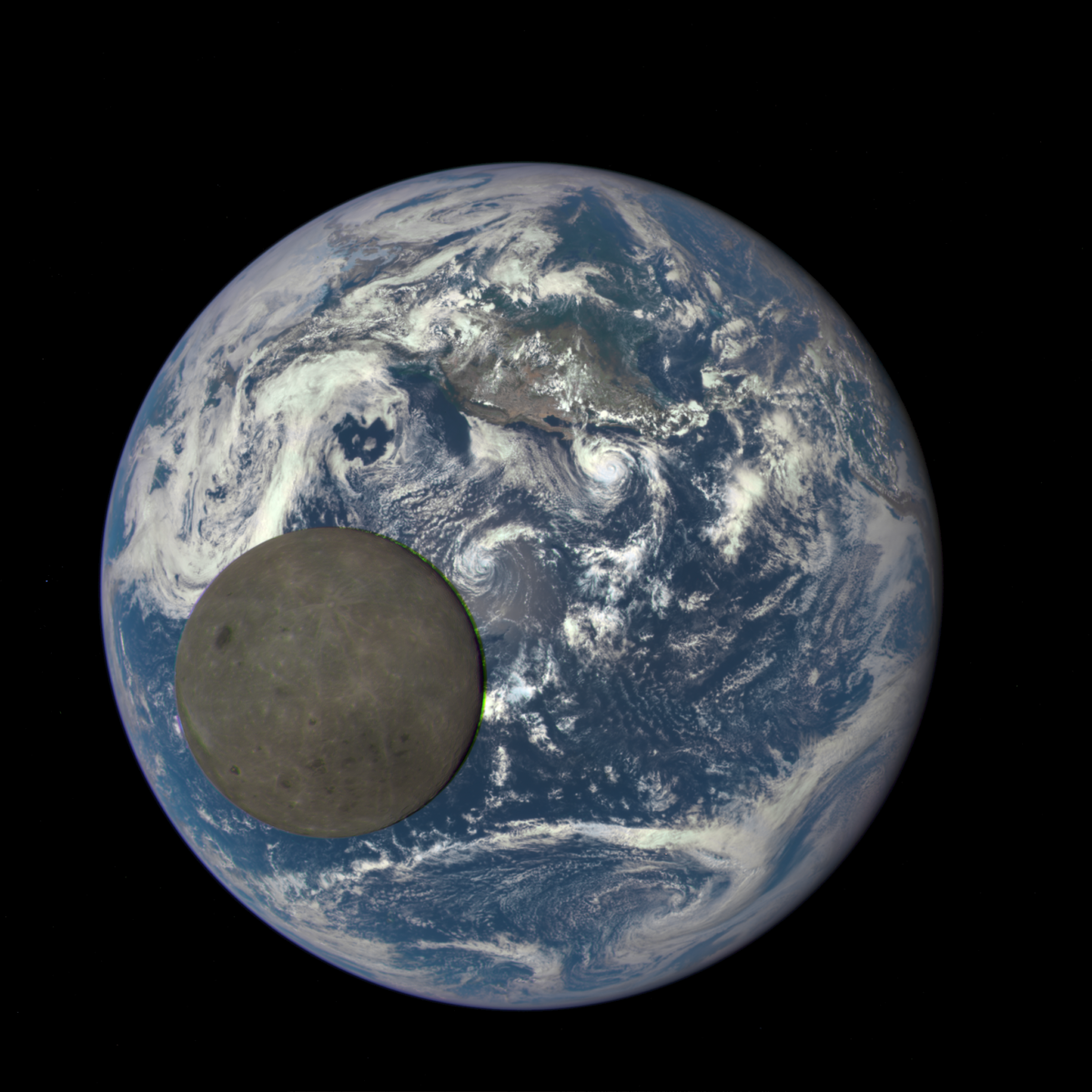

The Earth and Moon, captured together by the DSCOVR spacecraft. Credit: NASA/NOAA

Over the centuries, humans have tried to preserve their knowledge and treasures in various repositories, and some of these repositories were enormous in size. The library of Ashurbanipal, collected 700 years before the life of Jesus of Nazareth, is the oldest known collection of human knowledge. Ashurbanipal placed his collection of 30,000 cuneiform tablets in the ancient city of Nineveh, capital of the Assyrian Empire, in modern-day Iraq. Impressive as it was, its extent was dwarfed by another library of antiquity, the great center of learning at Alexandria.

The legendary Egyptian Library of Alexandria preserves much of the world’s ancient knowledge. Scholars and researchers from across the Mediterranean gathered there to make use of its spectacular 500,000 papyrus scrolls. Tradition holds that Julius Caesar accidentally razed the library during an attack on the nearby port in 48 BC, although other evidence points to a later disappearance. Regardless of the date, his loss was a tragedy for human culture.

Threats everywhere

The dangers threaten the survival of our modern culture and, perhaps, the existence of the entire human race. Ask the dinosaurs. A six-mile-wide (10-kilometer) space rock ended their 186-million-year reign on the planet, and many more asteroids are out there. (We’re doing a great job of tracking the big ones, but nature is full of surprises.) Toxic waste, ecological catastrophes, climate change, and global epidemics all pose existential threats to humanity.

Can an asteroid send us back to the Stone Age? Can an extreme pandemic rewind the progress of humanity by millennia? It’s the stuff of dark science fiction cliché, but the possibilities exist.

Now, however, copies of the greatest scientific discoveries and finest cultural and artistic masterpieces could be safely preserved in a world a quarter of a million miles away.

First steps

The concept has already seen a test flight aboard Intuitive Machines’ Odysseus robotic lunar lander, which landed on its side in February 2024.

Ulysses was part of the Artemis program to return humans to the Moon. On board the vessel was a data storage unit designed by Florida data startup Lonestar Data Holdings. Lonestar offers what they call Resiliency as a Service (RaaS) or “off-planet disaster recovery services” with “a series of increasingly sophisticated data centers on and around the Moon.”

The concept was inspired by a real-world event, says CEO Chris Stott: “In 2017, a cyber weapon of mass destruction was launched. It was called Notpetya, a Russian cyber weapon aimed at Ukraine. It deleted 80% of all data from their computers, in train stations, from the Ministry of Finance to hospitals to ATMs. But worse than that, it got out.” Notpetya fled to other networks within seconds, Stott says. “It almost took us back to the 1800s.”

Lonestar intends to protect the world from a similar future attack. Stott has been testing data backup in space since December 2021, when Lonestar and software developer Cannonical loaded the software onto Made In Space’s 3D printer drive aboard the International Space Station. That operation successfully ran AI, storage, and more.

Proof of concept

In February 2024, as a test of more robust service, the company beamed a digital copy of the Declaration of Independence through space to the Odysseus lander on its way to the Moon, and then again from the surface of the Moon itself. The spacecraft then returned digital copies of the Constitution and Bill of Rights to Earth.

Lonestar’s next mission is scheduled for the first quarter of 2025, again aboard Intuitive Machines’ next lander, this time occupying a full data center. Stott says, “The next step for us will be the first out-of-this-world physical data center, ever.”

But Stott’s team has much bigger plans: Working with terrestrial data center partners, a “living, breathing digital twin of the entire planet” is in the works, he says. The company’s next steps are into lunar orbit with the launch of a series of multi-petabyte data storage spacecraft from 2027 to 2031.

Eventually, Lonestar and its associates would like to build more permanent structures and have their sights set on lunar lava tubes. “There are more than 2,700 lava tubes,” Stott explains. “The one we’re looking at is one that’s 93 kilometers [58 miles] long, in the Marius Hills of the Ocean of Storms. It’s vast. You could put three or four Manhattans in half. And their natural internal temperature is minus twenty, perfect for electronics.”

Other efforts

The Arch project is exploring another version of global backup. With experience gained on the Moon, the organization’s Arch Mission Foundation initiative plans to create an archive of humankind’s knowledge across the solar system. Arch claims their design is “the largest footprint and longest lasting engineering project in human history.” Arch envisions a billion-year library archive established throughout the solar system.

The first Arch library was launched aboard Elon Musk’s SpaceX Tesla. In the glove compartment of the car, a copy of Isaac Asimov Foundation Trilogy it is engraved on a quartz disk. Architects predict that such digital records could last 14 billion years. Before Lonestar’s Intuitive Machines flight, another installment arrived at the Moon aboard the SpaceIL lander. That mission contained a 30 million page “civilization backup.”

The Moon also provides a convenient site for an extraterrestrial seed vault of Earth’s plant life, much like the Svalbard Global Seed Vault on the island of Spitzbergen. In 2017, floods threatened the structure of Svalbard as nearby permafrost began to thaw. A lunar warehouse would be immune to such terrestrial disasters.

Furthermore, the Moon’s great library could serve as a DNA repository for endangered creatures, preserving the genetic heritage of Earth’s rarest species. Biologists say the cold, stable temperatures in many of the Moon’s south polar traps could preserve the animals’ seeds and fibroblast cells. Fibroblasts can be transformed into stem cells for cloning endangered species. The researchers are now studying ways to protect the specimens from the radiation of the Moon’s south polar environment and hope to fly their containers on future missions.

The Artemis program, which aims to return humans to the Moon within several years, offers opportunities for such a project. A biological or digital treasure on the Moon could help future generations restore Earth’s biome and benefit from today’s best technology and wisdom.