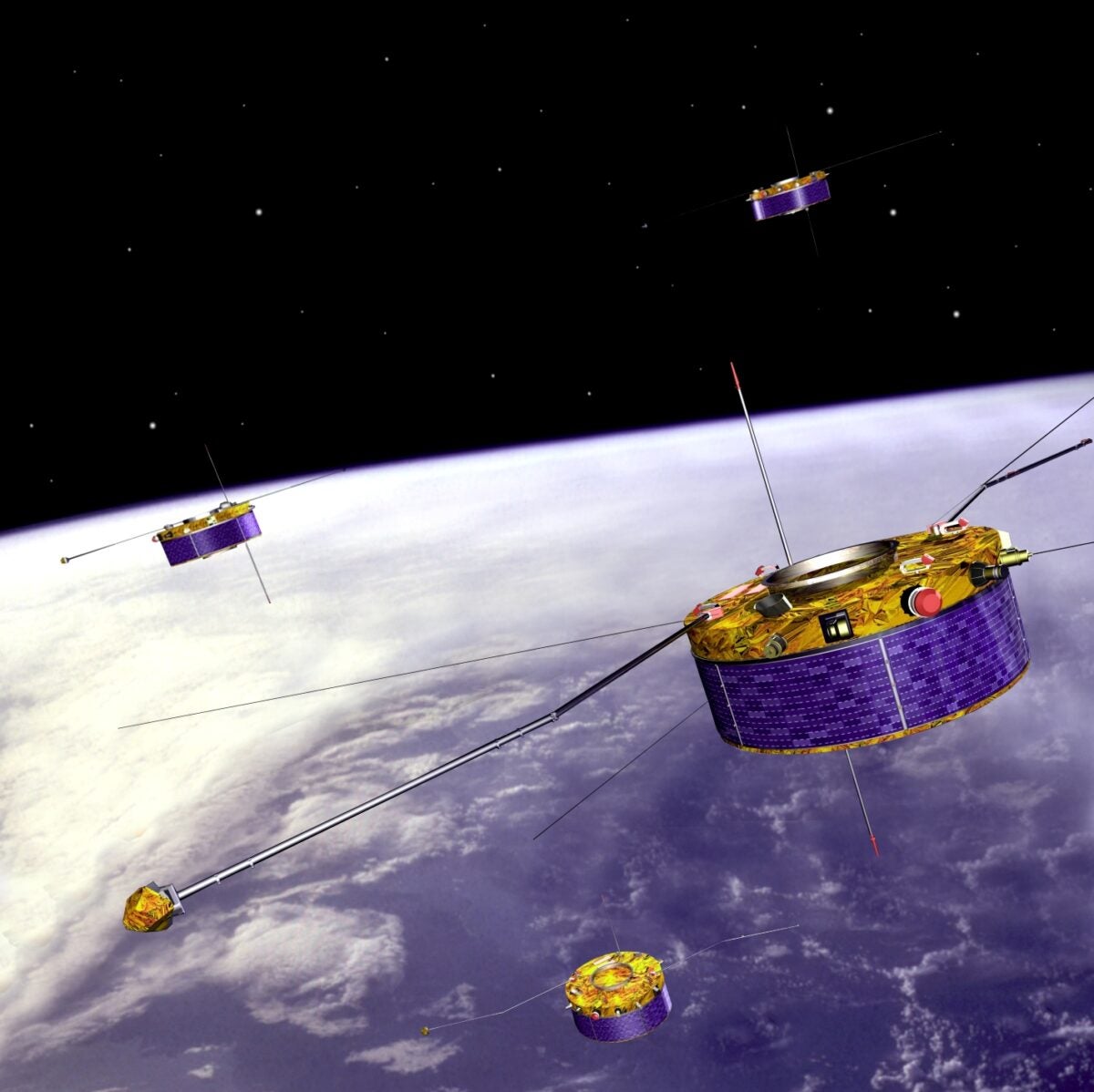

The four identical satellites of the Cluster II mission studied the interaction of the solar wind with the Earth’s magnetic field. Credit: ESA – CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

On July 26, 2000, the European Space Agency (ESA) launched the Salsa satellite, which joined its three companion satellites – Samba, Rumba and Tango – on the Cluster II mission, expected to last two years. On September 8, after more than 24 years of service, Salsa re-entered Earth’s atmosphere in a controlled deorbit, where it broke up over the South Pacific Ocean.

Cluster II was designed to study Earth’s magnetic field, specifically how the solar wind interacts with it to produce auroras and geomagnetic storms. The satellites have studied charged particles and magnetic fields across huge areas of the magnetosphere, from as low as 10,000 miles (16,000 km) above the Earth’s surface to as high as 120,000 miles (75,000 km), about halfway to the Moon.

Related: Are we ready for the next big solar storm?

Cluster II was a nearly identical replacement to the original Cluster mission, which was destroyed in a failed launch in 1996. Cluster II’s identical drum-shaped rotating satellites flew in a tetrahedral formation and could maneuver frequently, sometimes bunching up as close as possible possible. as 2.5 miles (4 kilometers), but usually extends about 6,200 miles (10,000 km) into space.

Each spacecraft carried an array of instruments to measure the energy and density of charged particles, electromagnetic fields and waves, and to perform analyzes of the stormy space weather conditions through which the spacecraft navigated.

The goal of these instruments was to study the small-scale structure of Earth’s plasma environment, in particular the solar wind-magnetosphere interaction. In particular, the mission was designed to map and study the various ways in which Earth’s magnetotail region altered its magnetic field and plasma conditions during the passage of a coronal mass ejection, an explosion of material that the Sun occasionally launches into space at high speed.

During strong geomagnetic storms, particle and field conditions vary rapidly in both time and space, making in situ measurements critical to understanding this activity. Cluster II performed these measurements with aplomb, providing data on more than two complete cycles of waxing and waning solar activity (a solar cycle lasts about 11 years). Researchers will be mining data for years to come.

Flying in formation

Cluster II was not the first or last mission composed of individual satellites operating in a flying constellation. Notable among these are the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES), which have been periodically upgraded and replaced since the first launch in 1975. GOES is responsible for monitoring space weather and Earth’s atmosphere and has also aided in research and rescue.

The five satellites of NASA’s THEMIS (Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms) mission were launched in 2007 to study magnetic reconnection in Earth’s magnetic field. NASA’s mission could vary the separation distance of identical maneuverable satellites to study many different scales of the magnetic reconnection phenomenon. While three of the satellites remain in Earth orbit, two are now orbiting the Moon, studying space weather.

And of course many communications satellites fly in formation, from GPS to Starlink, to provide coverage across the Earth’s surface.

A beautiful life

Cluster II was not designed to be operational forever. A satellite like Salsa cannot be allowed to remain in space at the end of its life to become debris for another spacecraft to collide with, nor can it be allowed to burn up in the atmosphere by pure chance, with the possibility that its pieces will fall over populated areas. Then ground controllers performed a series of maneuvers to send Salsa on a controlled re-entry on September 8.

Related: Small, untraceable pieces of space junk are cluttering low-Earth orbit

Even during their final months of operation and atmospheric reentry, the four Cluster II satellites offered scientists a place on the ring side to observe the mysterious region where charged particles are accelerated before producing the polar aurora. These regions are too high to be studied by balloon payloads and too low to be studied by spacecraft in low, stable Earth orbits.

The remaining spacecraft in the Cluster II constellation will be deorbited over the next two years, but with Salsa’s reentry, the mission’s science operations are over. Over 3,200 research articles on the scientific findings of Cluster II have been written and published to date, which will surely continue to inform for years to come.