The new Booster Shepard approaches the touchdown of April 14 during NS-31. Credit: Blue Origin

On April 14, 2025, Blue Origin launched six women – Aisha Bowe, Amanda Nguyễn, Gayle King, Katy Perry, Kerianne Flynn and Lauren Sánchez – in a suborbital journey to the edge of the space.

The titles called him a historical moment for women in space. But as a tourism educator, I stopped, not because I questioned their experience, but because I questioned the language. Were they astronauts or space tourists? The distinction is important: not only for accuracy, but to understand how experience, symbolism and motivation move today.

In tourist studies, my colleagues and I often ask for travel motivates and make it a significant experience. These women crossed a border leaving the surface of the earth. But they also entered a dispute over a symbolic: the blurred line between astronaut and tourist, between scientific results and well -kept experience.

This flight was not only the altitude they flew to – it was what it meant. As commercial space trips become more accessible to civilians, more people unite spaces not like scientists or mission specialists, but as guests invited or paying participants. The border between astronaut and space tourist is becoming increasingly blurred.

In my work, I explore how travelers find meaning in the way their travels are framed. A prospect of tourist studies can help unplanted as experiences such as Blue Origin Flight are designed, marketed and ultimately understood by travelers and by the tourism industry.

So, were these passengers astronauts? Not in the traditional sense. They have not been selected through rigorous NASA training protocols, nor were they conducting research or explorations in orbit.

Instead, they belong to a new category: space tourists. These are participating in a symbolic and realized journey that reflects how commercial space flight is redefining what means going to space.

Space tourism as a niche market

Space Tourism has its origins in 1986 with the launch of the Mir space station, which later became the first orbital platform to host non -professional astronauts. In the 90s and early 2000s, Mir and his successor, the international space station, welcomed a handful of civil guests financed privately – in particular the US businessman Dennis Tito in 2001, often mentioned as the first space tourist.

Since then, space tourism has evolved into a niche market by selling short encounters on the edge of the Earth’s atmosphere. While passengers on the NS-31 flight did not buy their places, the experience reflects those sold by commercial space tourism suppliers such as Virgin Galactic.

Like other forms of niche tourism – Wellness retreats, heritage paths or extreme adventures – the spatial journey appeals to those who are attracted to news, exclusivity and status, regardless of the fact that they have purchased the ticket.

These suborbital flights can last a few minutes, but offer something much more lasting: prestige, personal narrative and the feeling of participating in something rare. Space tourism sells the experience of being somewhere that few have visited, not the destination itself. For many, even a 10 -minute flight can satisfy a deeply personal milestone.

Tourist motivation and evolution of space tourism

Push-and-pull theory in tourist studies helps to explain why people may want to pursue space trips. Push factors – internal desires such as curiosity, the impulse of escaping or enthusiasm to obtain fame – sparkle the interest. The shooting factors – external elements such as the desire to see the vision of the earth from above or experience the feeling of lack of gravity – improve charm.

Space tourism draws on both. It is powered by the internal unit of doing something extraordinary and external attraction of a highly choreographed emotional experience.

These flights are often branded, not necessarily with flashy logos, but through the narrative and design choices that make the experience iconic. For example, while the new Rocket Shepard in which women have traveled do not bear a separate emblem, presents the name of the company, Blue Origin, in bold letters along the side. Passengers wear personalized flight suits, pose for preflight photos and receive patches or mission certificates, all designed to echo the rituals of professional space missions.

What is sold is an “astronaut for a day” experience: emotionally powerful, visually compelling and full of symbolism. But under the classifications of tourism, these travelers are space tourists, participating in a well -kept and short -lived excursion.

Marketing representation and experience

The image of the Blue Origin flight of six women aboard a rocket has been framed as a symbolic victory-a moment of girl’s power designed for visibility and celebration-but was also carefully treated.

It was not the first time that women entered space. Since its establishment, NASA has selected 61 women as astronaut candidates, many of whom give innovative contributions to the science of space and exploration. Sally Ride, Mae Jemison, Christina Koch and Jessica Meir not only entered space, but trained as astronauts and contributed significantly to the scientific, engineering and long -lasting missions. Their travels have marked historical results in exploring space rather than moments treated in tourism.

Recognizing their inheritance is important since commercial space flight creates new types of unique and tailor -made experiences, those modeled more by the performance of the media than by the scientific milestones.

The Blue Origin flight was not a scientific mission but was rather framed as a symbolic event. In tourism, companies, marketing and media experts often create these performances to maximize their visibility. Spacex has adopted a similar approach with its inspire4 mission, transforming a private orbital flight into a global media event complete with a Netflix documentary and an emotional narrative.

The Blue Origin flight sold a sensation of progress while mixing the roles between astronaut and guest. For blue origin, the symbolic value was significant. By launching the first crew of all females in the suborbital space, the society was able to claim a historical-a-a-a -ala milestone that has aligned them with inclusion-senza the cost, complexity or risk associated with a scientific mission. In this way, they generated enormous attention from the media.

Tourism education and media literacy

In today’s world, the spatial journey concerns the story that is told on the flight. From the images taken care of to posts on social media and to the press coverage, much of the meaning of the experience is modeled by marketing and the media.

Understanding this process is important – not only for scholars or professionals, but for the members of the public, who follow these trips through the narratives produced by the marketing teams and the media of companies.

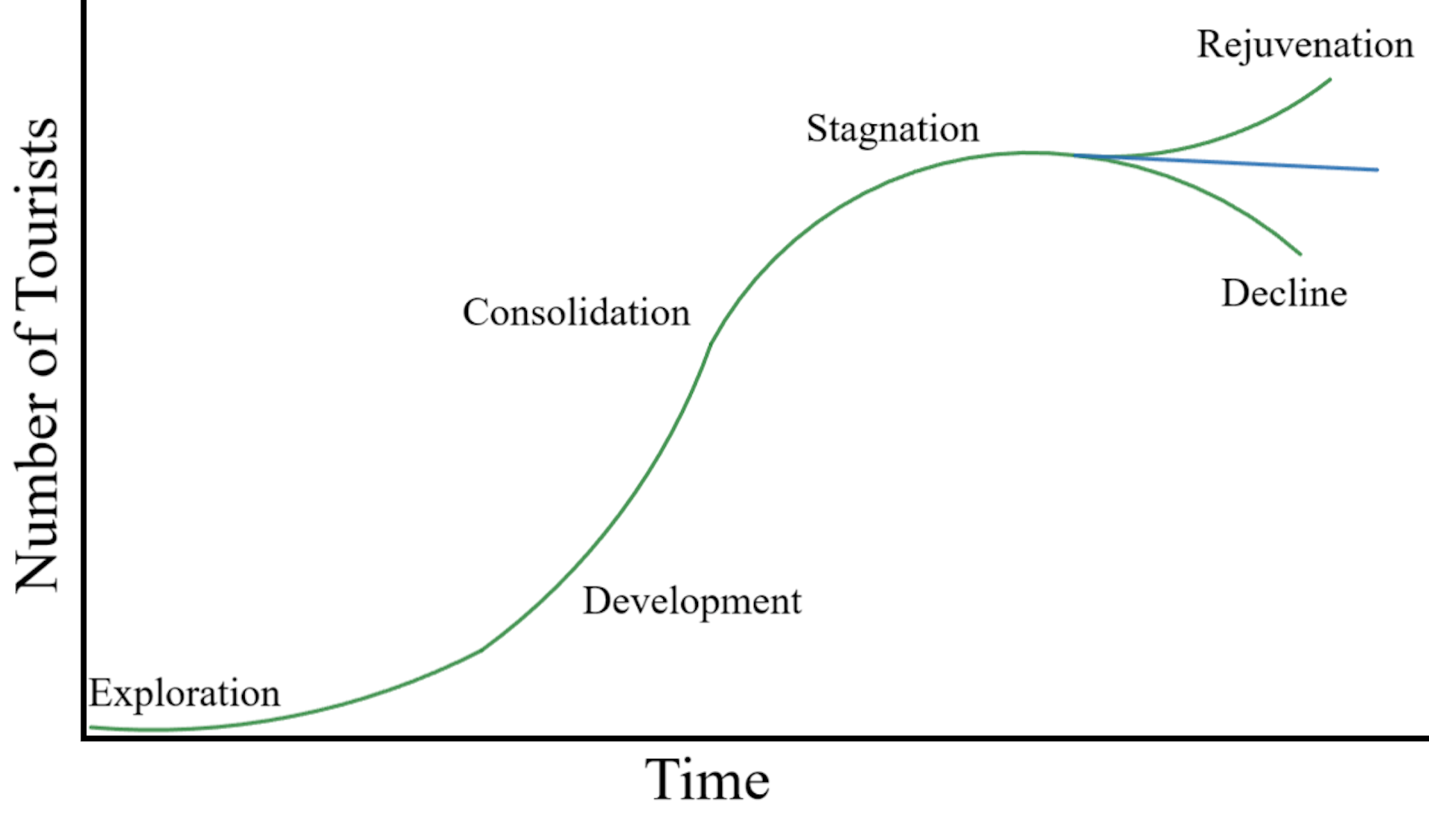

Another theory in tourist studies describes how the destinations evolve over time – from exploration, development, adoption of mass. Many forms of tourism begin in an exploration phase, accessible only to the rich or well connected. For example, the great tour in Europe was a ritual of passage for the aristocrats. His legacy has contributed to modeling and developing modern travel.

At this moment, space tourism is in the exploration phase. It is expensive, exclusive and available only for a few. There are limited infrastructures to support it and companies are still experimenting how experience should be. This is not yet mass tourism, it is more similar to a high -profile playground for the first to adopt, attracting the attention of the media and curiosity to each launch.

The progress of technology, economic changes and the change in cultural norms can increase access to unique destinations that start as outside the limits to most tourists. Space tourism could be the next to evolve in this way in the tourism sector. As is framed now – whoever arrives, how the participants are labeled and how their stories are told – will make the tone go on. Understanding these travels helps people to see how the company’s packages and sells an inspiring experience long before most people can afford to join the trip.

![]()

Betsy Pudliner is associate professor of hospitality and technological innovation at the University of Wisconsin-Stout. Pudliner is affiliated with the International Council of hotels, restaurants and institutional educators. The University of Wisconsin-Stout provides funding as a member of the US conversation.

This article is republished by The conversation Under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.